The ineffable power of place courses through artist Melissa Dickenson’s deeply affecting exhibition, Sonoma Charcoal: Rooted in Reverence, at K. Imperial Fine Art. In poetically abstracted landscapes on canvas and paper she exalts Northern California’s sumptuous countryside and coastline, integrating her materials and subject matter into a singular unified vision. This is a refreshing and impressive accomplishment, given that we generally associate the romanticization of place more closely with literature (the brooding north-English moors of Emily Brontë, the Morroco of Paul and Jane Bowles, the Tokyo of Haruki Murakami) and music (Dvořák’s Bohemia, Sibelius’s Finland, or Copland’s American heartland) than the visual arts. The most notable exception is the genre of landscape painting, with its inherent specificity. When we behold the craggy, mist-shrouded outcroppings on historic East Asian screens and scrolls, the majestic vistas of the Hudson River School, or Georgia O’Keeffe’s obsessive iterations of northern New Mexico, we are transported both geographically and psychically. What is so unique about Dickenson’s artworks, however, is that they not only project the viewer into a simulacrum of a beloved terroir, they actually physically transport that terroir to the viewer.

Melissa Dickenson, Shadow Valley, 2020, Sonoma charcoal, ochre, sandstone, limestone, and acrylic on canvas, 72″ x 84″

She achieves this mutual teleportation not via time machine or newfangled digital printer, but through methods as old as human and animal life: she forages. She is a veritable hunter-gatherer for art media. For the pieces in the current show, she hiked and drove the trails and winding roadways of Sonoma and Napa Counties, long renowned for their verdant, vine-strung hills, which yield some of the world’s iconic wines. The region more recently made headlines as the site of the Kincade wildfires of 2019, which raged for an agonizing fourteen days, scorching nearly 78,000 acres, destroying or damaging more than 120 buildings, and forcing the evacuation of nearly 200,000 people. Dickenson, who has many friends in the area, visited Sonoma in November and December 2019, shortly after the blaze was contained. There, venturing into devastated and denuded country, she carefully observed and gathered pieces of scorched earth, rock, madrone trees, and coastal live oaks, whose branches and trunks the fire had cooked into charcoal. With a field biologist’s meticulousness and a profound reverence for the land, she collected and catalogued these objects and transported them back to her studio in San Francisco’s Mission District, where she used them to create a new series of paintings in her signature style, first developed as she was earning her M.F.A. at California College of the Arts.

Melissa Dickenson, Mountain Nest, 2020, Sonoma Charcoal, Sonoma Clay, Mudstone, Ocher, Lapis Lazuli, and Acrylic on canvas, 48″ x 60″

A few months later, in the spring of this year, she returned to Sonoma and was heartened to find evidence of nature’s burgeoning regeneration: shoots and glades jutting out of ash as life returned in the aftermath of the inferno. The land was still deeply scarred, though, hills upon hills barren or ragged with blackened skeletons of once-resplendent trees. In this surreal zone between resurgence and hellscape she foraged for more charcoal and rocks, with which she subsequently created more paintings for the series. Her technique is complex, time-consuming, and labor-intensive, but it boils down to this: using a mortar, pestle, and if necessary, heavier-duty tools, she hand-grinds earth, minerals, semiprecious stones—and now burnt wood, soil, and rock—into fine pigment powders. After infusing these with a solvent, she pours them with a dancer’s precision and agility onto canvases laid out on the floor in the manner of Color Field painters such as Helen Frankenthaler, a major influence on her work. Sometimes she tilts the canvas while the paint is still wet to alter the gestures’ shapes and directionality, another nod to Frankenthaler but also central to the working methods of Morris Louis and Paul Jenkins. Dickenson layers gestures atop one another, using a spatula and other tools as she interacts with the unfolding composition. Exactly what any given pour will produce is impossible to predict with absolute certainty. Painter and paint engage in a spirited conversation, sometimes a battle. The resulting picture planes reflect this dynamic between expression and planning, unpredictability and control.

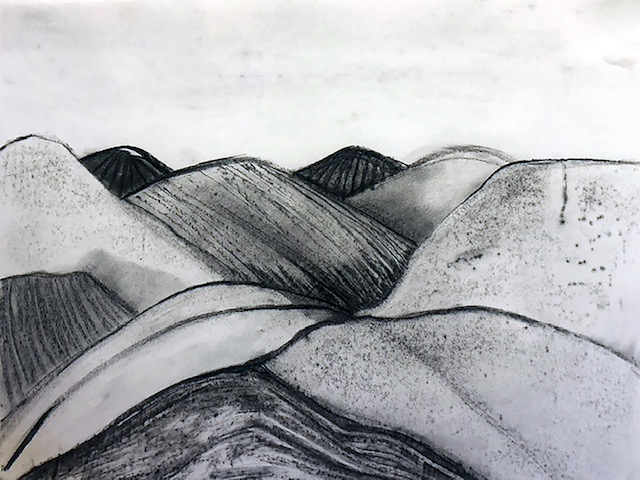

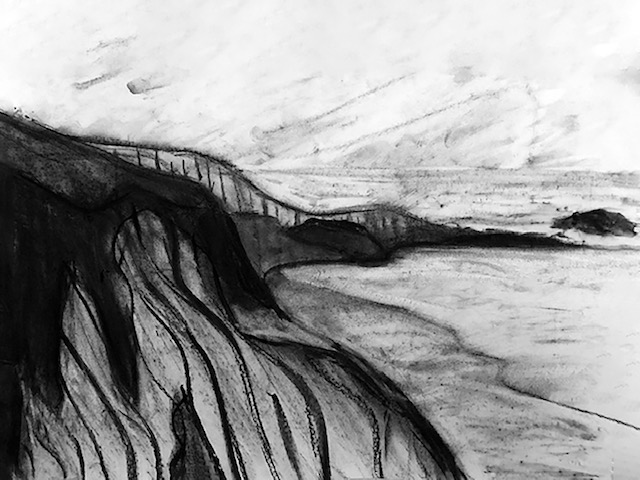

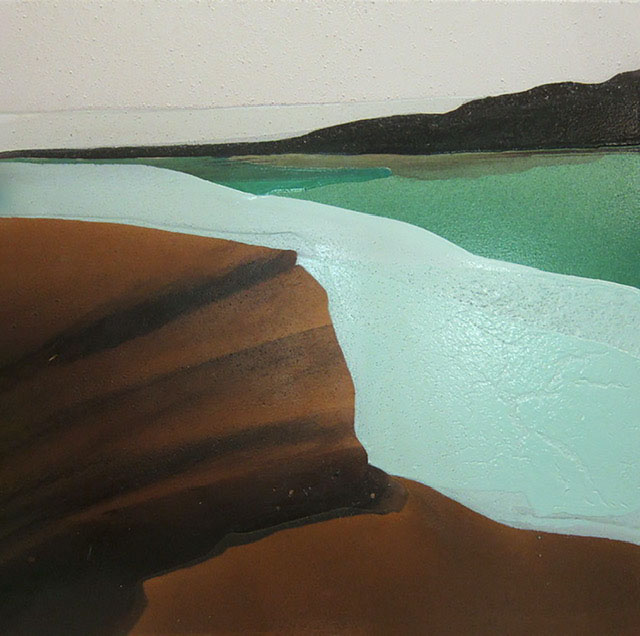

What emerges is pure lyricism—gracious, elemental forms that pay homage to the tangible and intangible magic of Sonoma: undulating ridges in paintings such as Shadow Valley and Alexander Valley, streams in Mountain Nest, waterfalls in Swimming Hole, the wide-open skies of Sonoma Cliff, and the milky sluice of cloud that crowns a tar-black mountain in Lake Sonoma. In a more intimate suite of charcoal drawings on fine cotton, the artist celebrates the region’s pastoral uplands, scenic highways, the surging Pacific crashing into cliffs, the Russian River lolling southward like a languid snake. Serene and meditative, each drawings is a vignette, a window, a portal into a daydream.

Melissa Dickenson, Sonoma Cliff, 2020, Sonoma charcoal, mudstone, sandstone, limestone, malachite, and acrylic on canvas, 40″ x 40″

Across the breadth of the drawings and paintings, surfaces whisper of whence they came, their rich textures by turns gritty, chunky, or silky-smooth with sand-grains, ground rocks, and charcoal residue. Within them Sonoma is palpable, quite literally. You don’t have to infer the landscape, it’s right there before you, loamy and porous, vulnerable but also resilient. Perusing the show as it’s installed on the gallery walls, you see the seasons turning, too, as the works made after Dickenson’s winter visit yield to those created following her spring and summer expeditions. The imagery edges from immaculate desolation to the tender, tentative reemergence of vegetation. These works are at once idylls and harbingers that remind us of the specter of climate change, for while the Kincade fire’s origins owed more to extreme winds and downed power lines than to global warming per se, other fires in Sonoma in recent years—to say nothing of those elsewhere in California and the wider American West—have without question worsened in frequency and severity as a result of the frought relationship between technological progress, climate, and ecosphere. That such diverse conceptual implications—materiality, site-specificity, the cycles of the year, the promise of rejuvenation, and the need for action to head off impending crisis—are embodied in artworks of such assertive physical presence, is a tribute to their maker’s gift for transmuting the very earth beneath our feet into thought-provoking, nuanced, and exquisitely beautiful objets d’art.

Melissa Dickenson, Lake Sonoma, 2020, Sonoma charcoal, mudstone, sandstone, limestone, ochre, malachite, and acrylic on canvas, 12″ x 24″

—Richard Speer is a critic and curator whose reviews and essays have appeared in ARTnews, Art Papers, Artpulse, Visual Art Source, Salon, The Los Angeles Times, and The Chicago Tribune. He is co-curator of the forthcoming exhibition Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing (LACMA, Spring 2021) and author of more than a dozen books, most recently The Space of Effusion: Sam Francis in Japan (Scheidegger & Spiess, 2020).